Hemodynamics

A. Velocity and Flow

Velocity = Volume flow / Area;

Volume flow (Q) = Velocity x Area

Volume flow will remain constant. Therefore, the velocity of flow depends on the cross-sectional area. Naturally, the velocity of flow will be low when the area is large, and high when the area is small. The same rule applies to blood flow in vessels.

B. Pressure and Flow; Velocity and Pressure

Flow is directly proportional to the pressure difference at the inlet and outlet (ΔP) for a rigid tube. If the tube is distensible like a blood vessel, the increase in flow becomes greater due to the increase in the vessel diameter.

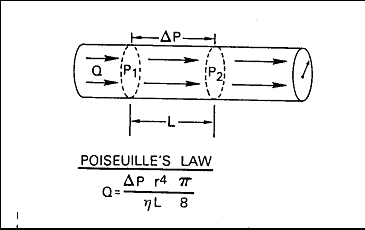

C. Poiseuille’s Law

Poiseuille's law: In an artificial system, flow through a cylindrical tube or any segment of a tube is directly proportional to ΔP, the driving pressure along the tube, and the fourth power of the radius, r. Flow is inversely proportional to L the length of the segment and to η, the viscosity of the liquid. The proportionality constant is π/8.

This law applies to an ideal system in which the flow is laminar and steady, and the fluid is newtonian. A Newtonian fluid would be a homogenious fluid. Blood is not a Newtonian fluid as it contains suspensions (red blood cells).

Blood flow through a rigid tube is analogous to electrical current through a wire with a certain resistance.

Ohm's law: I (current) = V (voltage) / R (resistance)

blood flow (Q) = pressure difference (∆P) / resistance (R)

Resistance expressed as PRU units: R=∆P/Q = 100 mmHg/5000 ml/min=0.02 PRU

(PRU= pressure-resistance unit)

In Poiseuille's equation, R=ηL/r4. Therefore, R is a function of viscosity of blood, the length of the vessel and the radius of the vessel. The fourth power effect of the radius changes on the resistance makes it the most important factor in the regulation of vascular resistance. In real life, blood flow and the vessel resistances are not steady but are phasic. Vascular "impedance" is the term used to describe the pulsatile resistance.

D. Importance of vessel diameter on flow; the r4 factor

A two-fold increase in vessel radius augments flow by 16-fold

A four-fold increase in vessel radius augments flow by 256-fold

Drugs that dilate the vessels therefore have powerful effect on blood flow.

E. Resistance in series and in parallel

Vascular resistances in series and in parallel.

Resistance in series: If across each series resistance, the driving pressure, (ΔP), is 3 mmHg and the flow (Q) 1 ml/min, then each resistance (R) would be ΔP/Q or 3 mm Hg/ml/min and RT (total resistance) = 9 mm Hg/ml/min.

Resistance in parallel: In parallel resistances, if across each resistance the driving pressure (ΔP) were 3 mm Hg and the flow (Q) 1 ml/min, then the total resistance is calculated as 1/R1 + 1/R2 + 1/R3 or 1 mm Hg/ml/min are in parallel, the total resistance is only 1/9 of that which would prevail if the three resistances were in series (i.e., the ratio of Rp/Rs = 1/9) so that it takes a ΔP of only 1 mm Hg (instead of 9 mm Hg) to produce a flow of 1 ml/min.

Conductance (C) = 1 / Resistance (R)

Therefore, for vessels in parallel, 1/RT=1/R1+1/R2+1/R3 = C1+C2+C3 = CT

F. Viscosity

One factor that determines vascular impedance is viscosity (η). The viscosity of blood relative to water is 3.6, mainly due to presence of red blood cells. In the circulatory system, viscosity depends on the concentration of the suspended cells such as red blood cells, white blood cells, etc, the velocity of flow and the radius of the vessel. The percent of cells in blood is called the "hematocrit".

-

The suspended cells exert frictional drag against adjacent cells and against the wall of the blood vessel. If the hematocrit increases (in conditions such as polycythemia or leukemia), the apparent viscosity of the blood also increases and the flow is reduced.

Hematocrit and red blood cells (RBCs). Left, The percentage of packed RBCs in the centrifuged blood samples, termed the hematocrit, is increased in polycythemia and decreased in anemia. The corresponding changes in hemoglobin content alter the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood. Right, Surface and cut views of red cells. RBCs sometimes gather into stacks called rouleaux which tend to offer increased resistance to flow.

-

Viscosity of blood increases as velocity of flow decreases. This is caused by the adherence of red cells to each other forming "rouleaux" stacks from erythrocyte aggregates at low flow. Also, at higher velocities, red cells travel more in the axial part of the stream whereas at low rates, the red cells distribute evenly and therefore produce greater net resistance to flow.

-

Blood flow in minute vessels (less than 200 μm in diameter; arterioles, capillaries and venules) exhibit far less viscous effect than in larger vessels. This is called the "Fahraeus-Lindqvist effect". This effect is caused by alignment of red cells as they pass through the vessels such that they pass as a single plug. This eliminates the viscous resistance that occurs when cells move randomly.

G. Streamline (laminar) and turbulent flow

Relationship between velocity of flow and turbulence

In a smooth, steady state flow, the flow is streamlined or laminar. This means that each layer of blood remains the same distance from the vessel wall. The central part of the blood remains in the center of the vessel and travels at the fastest velocity. Here, the pressure-velocity relation is linear. When the velocity of flow passes a certain critical velocity, the flow becomes turbulent. with swirls and eddies (similar to whirlpools in a rapidly flowing river at a point of obstruction). The flow may becomes turbulent when blood passes an obstruction in a vessel, makes a sharp turn or the inside surface of the vessel is rough even though the velocity is not high. All these factors increase the overall friction of flow in a vessel and therefore the resistance. Whether a flow is laminar or turbulent can be assessed by calculating the Reynold’s number which is dimensionless.

Reynolds' Number (Re) = (velocity of blood x diameter of vessel x density) / viscosity

If Re >1000 in blood, flow is turbulent.

H. Laplace’s Law

Laplace 's Law: Tension = (Transmural pressure x Radius)

Tension is force per unit length tangential to the vessel wall.

If the ratio of radius and the thickness of vessel wall is constant, then the wall tension will vary with the transmural pressure. This explains why capillaries with its low pressure needs only a thin layer of endothelial cells to maintain its wall tension. A weak wall will be likely to develop an "aneurysm" due to increased radius and thus the tension.

One can add the “wall thickness” factor to the LaPlace equation:

Wall stress = ΔPr/μ, where μ is the wall thickness. Wall stress will be less in vessels that are thick than vessels that are thin, if the pressure difference and the radius are the same.